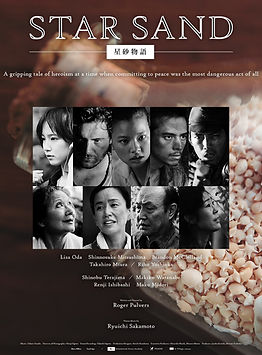

Star Sand is set on the southern Japanese island of Okinawa during the war. A young woman finds two men hiding in a cave: a Japanese army deserter and a debilitated American soldier (sensitively played by Australian actor Brandon McClelland).

This debut feature, based on a novel of the same name by Roger Pulvers, captures small moments in the progressive entanglement of these three lives – gestures, glances and shared silences. As their story reaches into present-day Tokyo, the film reveals the power of the past and the enduring pain of war.

With title music by pianist Ryuichi Sakamoto (best known for his work in “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence”), the film is impeccably visualized by an all-Japanese crew. Pulvers, a prolific novelist, playwright, and essayist formerly from Australia, has spent many years in Japan but now calls London home.

DIRECTOR’S NOTES – For the Seattle Wine and Film Festival 2020

It began in the winter of 1977, when I spent a month on a small island—less than one square kilometer in area—called Hatomajima, at the bottom of the Ryukyu Archipelago. Hatomajima lies some four hundred kilometers south of Naha, the capital of Okinawa Prefecture, which itself is more than one thousand five hundred kilometers from Tokyo.

I made two major discoveries while staying on Hatomajima: that the island was almost entirely unaffected by the ravages of World War II; and star sand. Not only beaches but also the seabed itself were, in many places, made up of these tiny carcasses of a protozoa that looked like tiny stars. It was hard to believe that any place in Okinawa could have escaped the war unscathed. The Battle of Okinawa had raged for nearly three months in 1945, creating more than one hundred and fifty thousand casualties on both sides. Little Hatomajima seemed like it was the peaceful and unmoving eye of a monstrous storm.

Five years later I found myself on another beautiful island in the Pacific that had escaped battle. Rarotonga is in the Cook Islands, located roughly below the Hawaiian Islands, in the Southern Hemisphere. It was there, in 1982, that we filmed Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, on which I acted as assistant to director Nagisa Oshima. To give you an idea of how isolated this location was, David Bowie, who played Maj. Jack Celliers in the film, told me that Rarotonga was the only place he had been where nobody recognized him, and he could walk around without a bodyguard. “It is marvellous to feel so free,” he said.

And it was Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence that led directly to the eventual production of Star Sand.

In January 2014 a documentary film was made for television about the making of Oshima’s classic anti-war film. Virtually all of the actors—including Bowie, Tom Conti, Takeshi Kitano and Ryuichi Sakamoto (who also composed the film’s score)—and major crew were interviewed. When I went into the studio for my interview, I had a reunion with the producers from the Hara Office who had handled production of Oshima’s film from the Japanese side. Oshima had passed away in January of 2013; and the documentary was as much an homage to him as it was a narrative about the making of a feature film.

It was in that studio that I proposed to the Hara Office that we collaborate on a film that I would write and direct.

Now, fundraising for a film and bringing it to completion is a little like waging a war itself: If you haven’t done it, you can’t really imagine how awful and gruesome it can be. During the succeeding two years, I made the rounds (an apt word, for it was at times much like running in circles) with cap in hand from CEO and CFO to people in medium and small businesses and sundry organizations. At every meeting I could see the neurons in my brain emerging by the tens of thousands from my ear, evaporating into thin air like so many tiny little star sands. Already in my seventies, I had never been in the position of eliciting funds for a project. Projects had, thankfully, seemed to come my way. But now it was “Death of a Salesman” at every encounter, with me, a greenhorn and rapidly aging Willy Loman, trying to keep my wits about me as best as I could, as my neurons were being lost forever to the ether…. Of course, my brave producers were working hard on the project as well; and a mere two years later (I have friends who have fundraised themselves from middle to old age without making a movie), they sent me an email from Tokyo to Sydney that read: “Alea jacta est.” Meaning “the die is cast,” this is what Julius Caesar apparently said to his troops just before leading them into battle across the Rubicon. We had the funds and there was no turning back. I would venture to say that this was the first time a Japanese film production company had ever announced success in fundraising to a director in Latin.

Fortunately, the novel Star Sand, which I had written both in English and Japanese, was published in the interim in both languages by two large publishing houses, Amazon and Kodansha … and both versions were being received well. The English-language version has recorded over a thousand reviews on the U.S. and the U.K. Amazon sites. This gave impetus to the production. In addition, I have met and worked with many Japanese actors over the more than fifty years that I have been in Japan. With an exceedingly limited budget, friendship—and the trust that it naturally engenders—counts for a great deal. Two of Japan’s greatest veteran actors, Renji Ishibashi and Mako Midori, both legends in Japan, said they would appear; and my dear friend Ryuichi Sakamoto graciously acceded to writing the theme song.

I approached the younger actors, who I hadn’t known personally, and they were kind enough to take on parts. Oshima had once told me that casting was seventy-five percent of a director’s job. With me, I felt that it was closer to a hundred. It wasn’t the money that attracted the actors, that’s for sure. Star Sand was made on a shoestring, and a very short one at that. Long after the shoot I asked a few of them why they took on the roles. They all said the same thing, that they were attracted to the story of nonviolence, a story not about the enmities between foes but the affinities. I am not ashamed to say that I had tears in my eyes. If my entire writing career, spanning five decades, has been dedicated to one thing, it is that no form of violence whatsoever, be it directed at an enemy or any other person, is conscionable. War produces only victims on all sides.

So, at the beginning of June 2016, we set out for Iejima in Okinawa. Hatomajima, the location of the story of Star Sand, was too remote for a film shoot. The bitter irony of shooting on Iejima was that that island had been entirely decimated and flattened during the war. In fact, not one single home on the island, where nearly five thousand people were living, remained. The only structure that was partially intact was the concrete Public Pawn Shop, which became, in our film, the uncle’s storeroom where Hiromi found the first-aid kit.

In filmmaking the only thing that costs real money is time; and our shoestring had to be stretched tightly to do the job. All in all we had only twenty-one days from the first day of principal production (that is, the shooting of the first scene) to the wrap, and this had to include movement not only around Okinawa but also from Okinawa to Tokyo, where the contemporary scenes were shot … and pick-up days, which are incorporated into the schedule in case something goes awry. In the end, I shot Star Sand in fifteen days of photography. The intensity of passions connected with creating a film was exhilarating, and I skyped my wife from Iejima to Sydney every day to say that, at least there and then, I felt that I had been waiting seventy-two years for these exquisite moments.

After the wrap, the editing process began, lasting the entire sweltering Tokyo summer of 2016. I had promised my producers before we began that I would deliver the film—edited, color corrected, soundtrack laid, credits in place, subtitles included, the whole kit and caboodle—by six p.m. on August 31 … and forty minutes before the deadline, it was done and ready to screen. What had begun as a reunion at a studio two years and seven months before was now a completed feature film. A miracle in some ways, yes; but more than that, a tribute to the dedication and passion of my producers, actors and crew who brought the story to the screen.

Over the decades I had directed dozens of plays in Japan and Australia; and working with actors and staff on those plays had been a supreme joy. Though a film requires many different approaches in acting style, lighting, sound and set decoration compared to a drama on stage, the primary task is the same: How to tell a story that travels from the inner life of the characters to the inner life of the person watching them. Despite all of the technical wonders that filmmaking has at its disposal, the communication of essential messages of compassion, empathy, love and devotion to one another—particularly at times when those qualities are being tested—remains the core preoccupation of those of us who are lucky enough to have the chance to be a medium for them.

Roger Pulvers

Sydney

November 2019